Marzipan is yummy. But how much marzipan is too much marzipan?

Imagine you owned a Marzipaniter, a device that generated as much of the stuff as you wanted. All day, every day, an endless tube of sugary almond paste at the touch of a button. How would that change your attitude about marzipan?

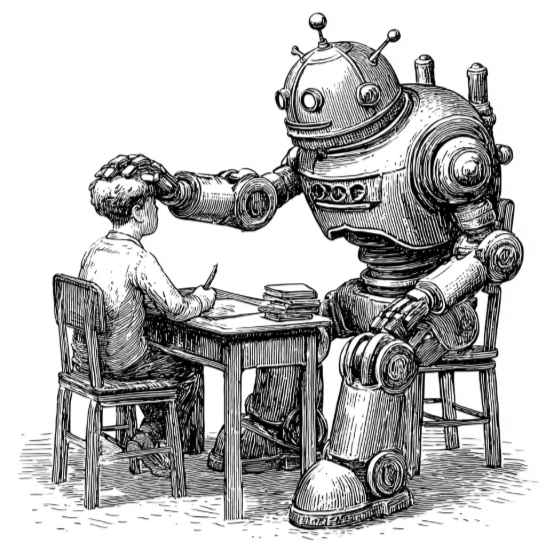

Now imagine, next to your Marzipaniter, you had a Shakespearion. Every time you pressed PLAY, a brilliant new drama would emerge. And for this thought experiment to work, you have to imagine that each play is truly good. Not ironically wink-wink pretty-good-for-a-machine good, but amazing. Beep, whir… King Lear. Beep… Hamlet. Beep-boop… Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Both of these devices seem far-fetched. But I regret to inform you that the Shakespeare Button is closer than you might imagine. It’s worth taking seriously long enough to think through the implications.

Artificial intelligence has made it possible to generate not just copious amounts of what is being called “slop”. It’s also being used to generate copious amounts of really good stuff. Just today I was talking to my friend Mike at work about AI and software. We were discussing a certain professor on LinkedIn who was, with the assistance of AI, releasing vast amounts of software. Truly volcanic output. I pointed out that the software appeared to be quite good. Mike said it was annoying. It was noisy. Regardless of its quality, its volume robbed it of the designation “excellent.”

How much does your concept of quality depend on scarcity?

We’re moving, and moving quickly, into a world where there will be an endless torrent of AI-generated content. And as Sturgeon’s Law tells us, 90% of everything is crap. But old Theodore Sturgeon himself had no interest in dwelling on that part of the equation. The remaining 10% is gold. The glass isn’t 90% empty. It’s 10% full. If we apply this adage to the age of infinite AI-generated content, then you can do the math: 10% of infinity is… quite a lot. You see? Even if you feel compelled to discount my 10%, an infinite amount of really good stuff is coming your way. Perpetual novelty piped into your sense pots every minute of every day.

What I want to know is how you feel about it.

This is a world of quality inflation, where mere talent feels cheap. It’s disorienting, because it threatens to invert our notions of effort and mastery. But that thumping anxiety in your chest will pass. We already live in a world of endless excellence. Do you ever get bookstore anxiety? That panicky overwhelm of too many good books and not enough time? It’s the same thing. But it passes. There’s no need to feel sad about an infinite amount of good content you’ll never consume. As a practical matter, we’re already there.

And here is the thing that will empower you: in a world where excellence becomes abundant, what becomes scarce? As other people’s content gets cheap, it’s your attention that gets expensive. Congratulations! You control one of the most valuable assets in the New World. And it will only get more valuable.

Content doesn’t command you. It conforms to you. To your intent and attention. Your eyes set its price. When you adopt this attitude, you realize that you no longer need to be intimidated by bookstores or AI slop-shops. They tremble at your power! They hunger for your lifegiving gaze. You’re in the driver’s seat. They are your scenery. Enjoy the ride.